K/DA. Credit: Riot Games

Authors note: If you are working on a project or on a start-up in this niche, I would be very interested in hearing from you.

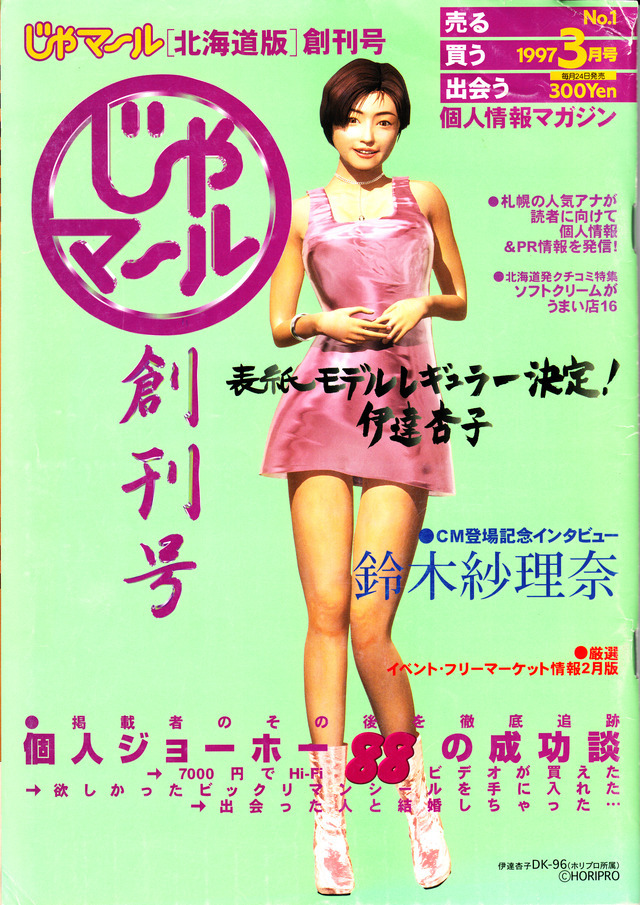

Just as the Spice Girls were dominating the airwaves in the late 90s with the 90s “girl power” movement, a vivacious and ambitious female artist in Tokyo was planning to make her own mark on the Japanese pop scene. Scouted by industry professionals while working at a hotdog stand, Kyoko Date’s career advanced quickly. It began with an electric track, “Love Communication”, released by her management company Horipro in 1997. Horipro had huge ambitions for Kyoko Date, so, there was disappointment amongst Kyoko Date’s team when her first single did not set the world on fire. Kyoko Date was not so downbeat. In fact, Kyoko Date did not feel anything, mainly because she was a fictional, animated character created by Horipro.

In this essay, I will argue that Horipro were on to something big. It will be a major revolution in computer graphics, holographic media and sound. This is made possible by the “real time raytracing revolution” (R3), a quantum leap in computer graphic power. R3 will occur when raytracing becomes the dominant form of real-time rendering, thus allowing computers to create incredibly realistic computer graphics in real-time. Although Horipro regarded the Kyoko Date project as a humiliating failure, this essay argues that Kyoko Date was the first inkling of the next megatrend in the media.

If you follow the technology industry, you might ask – why write this essay? Everyone knows that avatars will be big in the metaverse, don’t they? While it seems that many start-ups are creating virtual idol groups, I have noticed that many founders struggle to articulate why the virtual artist revolution is upon us. This is because expertise in disciplines such as 3D graphics, game engines and “idol culture” is required to make sense of it all. For this reason, it is easier for founders to use the “metaverse” as a justification for their projects, because it is buzzy and widely accepted as an emerging tech trend, rather than delve into the complexities of computer graphics, or break down the inner workings of the idol industry.

This essay aims to explain in vivid detail why we are hurtling towards a holographic future where the virtual artist reigns supreme. This will be a world in which reality and real time ray-traced holograms are inextricably bound together and are often indistinguishable.

I begin with the history of virtual artists, examining how projects like Kyoko Date, Gorillaz and Hatsune Miku struggled with fulfilling their original vision, due to the high cost of 3D animation, the enormous challenges of producing live holographic content and the difficulties corporations face in producing virtual artists. Next, I explore the rapid advances in game engine technology, and how they enable low-cost 3D animation production. Lastly, I examine how the declining cost of 3D animation and rendering will dramatically lower the cost of producing virtual groups. Finally, I reflect on the rise of holographic media which will enable virtual bands to be monetized in a way that was never possible before. Once you have finished this piece, you will agree that this is not a passing trend:

It's the dawn of the virtual artist.

In the opening section, we will examine the different types of virtual artists that exist today. We look at artists with avatars, avatar-native artists and third-party virtual artists. Once we finish with the definitions, we imagine the development process for developing an artist of our own. By the end of the section, you will agree that the development of virtual artists is both efficient and cost-effective!

In today’s world, it is difficult to determine where the digital world ends and the real world begins. If you talk with someone on Twitter, are you friends IRL? If a deep-fake viral article affects a politician’s election changes, does the fake news not become real? Are AI virtual assistants not just assistants? The same question applies to virtual stardom. If artists around the world use Instagram daily, are all artists not virtual? To this end, it is useful to have a clear definition of virtual artists. For me, a virtual artist is an entity whose identity and presence are primarily represented or expressed through 2D or 3D computer graphics. The graphics can be of varying quality. They could be a manga-style animation which is not real. Or they could be highly realistic 3D renders. Nevertheless, they should all come under the banner of animation.

An artist using an avatar is the most basic virtual artist. It refers to a regular human artist who uses a 2D/3D avatar to represent themselves for specific occasions. If Taylor Swift played a concert in Roblox, she would be an artist using an avatar. The avatar is a visual aid for a specific occasion. Regardless of whether the avatar appears on stage or in a game, it is evident to the audience that the avatar physically represents the real life artist. When an artist uses an avatar for a specific purpose and not merely as an aesthetic prop, they are considered an artist with an avatar. Another example of this is AESPA, the K-pop girl group from Korea. The members have digital avatars for online events, but the avatars represent the artist in the digital world.

Aespa. Credit: SM Entertainment.

The Avatar-Driven Virtual Artist is the next step up. This group consists of genuine human artists who primarily appear as avatars. The avatar could be used to give the act a unique image, or it could be a way to shield the artist from the harshness of the limelight. Even though they appear as animated characters in videos or on streams, it should still be clear to the audience that there is a real human being behind the animated character. The Korean-produced Plave is a brilliant example. It is a five-man Kpop boy band with members Noah, Bamby, Yejun, Eunho, and Hamin. Although the band appears in animated form, they are real artists. Audiences love to know that there is some human component to a project. One of the top comments on the video of Plave’s debut captures this sentiment nicely: “I hope the real vocalists are able to enjoy a happy, successful life pursuing their passion behind the anonymity of these beautiful characters”.[1]The human element is critical in balancing the virtuality. On the other hand, the virtual artist projects with no human element or no sense of human input often repel audiences. This is something we will look at later on.

PLAVE. Credit: Asian Junkie.

Readers might also ask if it is necessary to make the distinction between artists using an avatar and Avatar-Driven Virtual Artists. It is just the same, no? They are almost the same, but the economics of developing the acts are different. Acts that appear primarily in virtual form do not need to undergo extensive dance training, and they do not need cosmetic changes. This makes the development of this kind of act cheaper and shields the artists from some of the harsher aspects of the idol industry.

Animated Virtual Artists do not represent a real artist in a literal sense and fall along a spectrum. On the one hand, there are animated artists that are clearly fictional. On the other end of the spectrum, there are AI-style avatars that look like humans. This category are hyper-realistic avatars that look almost indistinguishable from humans. They are completely computer-generated and usually owned by a company.

Fictional Virtual Artists usually exist in their own fictional universe and do not represent the artist directly. By way of example, 2-D from Gorillaz is not Damon Albarn. 2-D is a completely fictional character. The act may be produced by a corporation, or musical artists like Gorillaz (or Major Lazer). These characters are often more costly to produce and usually require a team of animators, software engineers and 3D designers to create. Apoki is another act that springs to mind in relation to the Fictional Virtual Artist. Apoki has released some cool songs and is produced by a company specializing in 3D graphics. It is clear that this character exists in her own fictional universe. K/DA is another great example of fictional virtual artists. Produced by Riot Game’s for League of Legends tournament, K/DA are a four-person fictional artist girl band with a slick animated aesthetic. These characters are animated and should be obviously fictional for the audience. Avatar-Driven Artists and Fictional Virtual Artists are very similar. So how can you tell the difference? The key is in asking: who is the artist? If the artist exists in their own fictional universe, it is a Fictional Virtual Artist. If the artist represents an actual artist, they are an Avatar-Driven Artist.

Humanoid Virtual Artists are the final category we will explore. They are highly realistic 3D avatars that look indistinguishable from real human beings but do not represent a real-living person. In essence, they are high-quality 3D renders. These characters are always “AI”, but they are often referred to as “AI” artists. Sometimes they are generated as 3D renders, other times they are created using simple AI tools. There is much fanfare about this category. After all, they look like humans but cost far less to use. They can also never be cancelled, and you can create them however you like. Each of these things might be considered a blessing; however, they can easily become a curse as well. While teams can create any artist they want, they will need to please all backgrounds with their character which is impossible. Bernila.gram was a virtual influencer from the Philippines who got enormous flak for not looking Filipino enough.[2] While virtual artists cannot technically be cancelled, they can be dropped from their labels. This happened to digital rapper FN Meka when the project was called out by the black activist group “Industry Blackout” for insensitive racial stereotypes.[3]

Bernila.gram. Credit: Next Shark

AI tool

Another difficulty with these AI-style artists is that they often look like humans, except they are duller. In social media content, it is often the imperfections or spontaneous actions that make something interesting, and these moments cannot be engineered easily. This creates situations where animation teams are bending over backwards to create a natural moment that a human influencer creates in one second for free. One final issue with real-style virtual artists is the sky-high costs of producing 3D-rendered images. A company that uses game engines or CAD software to model and present their characters could spend between $500-$1,500 per render and they must produce a stream of renders for social media.[4] The virtual artist’s team is therefore incentivized to avoid taking risks on renders considering how expensive each render is. This makes it even more likely that the AI-style artist will be dull. AI can produce highly realistic images, but I have not encountered AI tools that incorporate 3D well. This means that the team cannot plug into the vast tool-set provided by game engines. Overall, I am not convinced that AI-style virtual artists will take over. People are unnerved by them. The cost of rendering these real-life 3D characters will indeed decline rapidly, making it cheaper than using real human beings. So maybe AI influencers will have their day then? It could happen, but I am not convinced.

This essay makes the case that Animated Virtual Artists will be one of the major winners of the virtual artist revolution. There are numerous benefits to using Fictional Virtual Artists. They exist in a separate fictional universe and this makes it possible to create a transmedia franchise. We see early signs of this with Gorillaz in talks with Netflix to create an animation series.[5] Fictional virtual artists theoretically never die and so the brand power can compound indefinitely over decades, or even hundreds of years. Real bands get sick of each other and split up, but virtual bands don't. When Damon Albarn compared Gorillaz to Star Wars it might have sounded off, but it is a good analogy - they are similar.[6] Fictional characters and artists are also more interesting than normal artists, at least visually. 40,000 tracks are uploaded to Spotify daily.[7] I imagine almost all of them are by regular, human artists. If you show me an artist picture on Spotify of a man with a mullet, I will think to myself - ”he probably plays guitar”, but I won’t be interested. If you show me an artist's picture of an elf-like animated character, I am drawn in a bit more - "What could she sound like?”, "Where is she from?", "who created her?". Today, fictional artists are difficult to monetize. Even if you make a hit song, it could still be difficult to recoup the high costs of animation through streams alone. The second part of my thesis is that we are entering an era in which holographic media will morph from a niche idea to a dominant class of media. In this world, it will be significantly easier to monetize fictional bands and all of the benefits of holograms will come into play. We will examine how fictional artists are cheaper to produce in the next section. Finally, fictional artists can be owned as intellectual property. This is especially significant in the music industry because you cannot ”own” an artist. If you manage an artist and take their record to number 1, is there anything stopping them from leaving you? No.

Avatar-Driven Virtual-Artists will soon have their day in the sun, but for different reasons. Gen-Z is the most online generation in history. No generation has been raised as they have under the harsh glare of social media. As a result, Gen-Z is much more focused on mental health. I suspect that artists marketing themselves as ”avatar-first” will resonate deeply with Gen-Z’s fixation for mental health protection. Gen-Z will appreciate an artist who can avoid the perils of social media while still building their audience. Avatar-Driven Virtual-Artists are like the anti-social media artist, the social media protest vote. Their decision to use an avatar is a rejection of the popularity contest that all social media becomes. Another benefit of Avatar-Driven Virtual Artists is that they are very cheap to produce. Whereas the K-pop model involves training idols for years in boot camps, the Avatar-Driven Virtual Artists just need a team to animate the dance moves. Many will argue that it is not the same thing - the virtual artist is fictional and is not real. But the animations used for the virtual artist do come from somebody human at some time. It is not so different from a pop idol miming lyrics to a song they recorded earlier. Avatar-Driven Virtual Artists are costlier than just producing "AI” style artists, so why bother? In many of the YouTube videos of virtual artists I have watched, there is very often an appreciation of the human element as well as a distrust of the digital side of a project. The more humanity is eradicated from a project, the more audiences pull away. Even if an artist is completely fictional, audiences will often appreciate the animation and animators behind the project. The highly realistic fictional 3D artists have the least amount of humanity which is why I am extremely wary of this category.

In sum, there are four categories of virtual artists – Artists using an avatar, Avatar-Driven Virtual Artists, Animated-Virtual-Artists, and Humanoid-Virtual-Artists. Of course, after reading everything, you'll probably think - are all the definitions necessary? I strongly believe they are necessary because each category is faced with advantages and disadvantages that only apply to them. The artists using an avatar are regular, human artists. They reap very few of the benefits of the virtual artist revolution. These artists are regular girl or boy pop groups that are trained in the traditional, costly way. They must now go up against artists who can do almost the same things as them for much less. The Avatar-Driven Artists do not require any of this training and can use real-time technologies to their advantage, but they can still maintain an intimate, human connection with their fans.

Animated Virtual Artists are the only category that can develop into a fully-fledged transmedia franchises. I also believe that they are the only category in which creative companies can thrive because animation requires high upfront costs and the company then owns the intellectual property. This leaves us with the final category - Humanoid Virtual Artists. I am deeply pessimistic about this category overall because I believe many consumers will be alienated by their lack of humanity. I also think that projects often walk a tightrope regarding diversity because it is impossible to ensure everyone is represented as a virtual artist. If the virtual artist is an elf, for example, they do not have this problem.

In the next section, we will track the history of virtual artists. We will explore two projects in particular detail – Gorillaz and Kyoko Date. By following the historical trajectory of virtual artist development, we uncover the common pitfalls in the development cycle. This is especially important because, in the following section, we explore how the rise of real-time technologies can assist where previous virtual artist projects failed, namely in the production of high-quality animation.

Kyoko Date. Credit: Hori.

Let's go back to Kyoko Date. Horipro's Kyoko Date project was based on the problems the talent agency had with developing artists. Horipro knew firsthand the challenges that came with managing idol groups. You invest enormous sums in them with no guarantee of a pay-off. Managing the artists themselves is akin to walking a kind of tightrope, where even a minor PR disaster can end a career in seconds. Despite the enormous risks and high risk of failure, the most successful artists have a limited shelf life as they grow less attractive with age. Nevertheless, Horipro were not short of ambition, and one of the creators confidently stated "Technology will enable Kyoko Date to appear on a live TV show and chat with other artists”[8].

The team hired a three-man computer graphics team to develop the character. Kyoko Date's debut in 1996 did not generate much interest in Japan as the idea of a virtual idol did not resonate with the Japanese public, and Kyoko Date was discarded quickly. It was not until the Western media picked up on the project that Horipro received a flood of interest in Kyoko Date. She went viral in America and Europe, and the bulletin boards on the project's website were flooded with interest from guys in Italy, Hong Kong, and Malaysia. The media were, however, more interested in the concept itself than Kyoko Date's music. After 10 months of activity and 1 year of inactivity, Horipro shut down the Kyoko Date fan page forever.[9] The last ever post on the bulletin board was matter-of-fact: “I've decided not to update this page anymore. Thank you to the 100,000 people that saw my page and enjoyed it!!!!”.[10] After Horipro removed all information about Kyoko Date from their website, it is clear that the project was deemed to be a humiliating failure. Many people today still think the concept envisioned by Horipro is a fundamentally unserious idea. This is because you must understand the mechanics of the Japanese or Korean pop idol business to understand the benefits that come from developing a virtual artist. Otherwise, the logic does not make economic sense. Producing idols is very costly and there are a litany of reasons why an artist’s career can fail. Virtual artists are different, however. Firstly, virtual artists never get sick or are involved in scandals. Secondly, they can appear in multiple places at once (via holograms, once the technology develops). Thirdly, they can speak and sing in any language. Lastly, they last forever allowing the brand power to compound over time.

While the logic of Horipro’s idea made sense, Kyoko Date was hindered by the substantial cost of 3D animation. One Horipro executive remarked that it cost several million yen per minute to have her sing live (3 million yen is roughly 20,000 USD in today’s currency).[26] Even when 3D animations were composed, they were clunky. In her 1997 debut, ”Love Communication”, her movements are staggered and not believable. Many critics at the time left it at that – virtual artists were a gimmick with no real shelf-life. These people were not animation experts and did not realize that the advance of Moore’s law would dramatically lower the rendering of 3D animations as the 21st century progressed. The core argument of this essay is that Horipro’s virtual artist concept is not a gimmick. It is the future.

Credit: bcheights

In 1998, two virtual artist projects began where Kyoko Date left off. One act was AdamSoft, a 22-year-old Korean crooning over a K-pop/love ballad. The other project was created by two flat-mates in London who hated each other. One flat-mate was pretty into animation, the other flat-mate was the lead singer of the UK’s most popular rock band. Damon Albarn and Jamie Hewlett had a pretty simple idea - to create an animated band that commented on celebrity culture. In Albarn’s own words:

“I've grown tired of the celebrity aspect of being in a band. It just kind of became an all-pervading thing”.[11] Hewlett later gave his own insights into the forming of the group: “If you watch MTV for too long, it's a bit like hell – there's nothing of substance there. So we got this idea for a cartoon band, something that would be a comment on that."[12] There would be four fictional characters – 2D, Murdoc Niccals, Russel Hobbs, and Noodle. They would have their own elaborate backstory, except they would not be produced by a company or 3D specialists and they would focus on making great music. The name of the band? Gorillaz.[19]

Hewlett later gave his own insights into the forming of the group:

“We tried the holograms when we did the Grammys with Madonna, and it looks great on television. But the problem in real life is that when you turn the bass up too loud, the invisible screen that reflects the holograms starts to vibrate, and they fall to pieces. So you have to play very quietly, and nobody wants to see a quiet concert - Jamie Hewlett”.[19]

Today Gorillaz is an enormous success. They have sold 33 million records to date.[13] They are the world’s most successful virtual band according to the Guinness book of world records.[14] Casting Gorillaz musical accolades aside, Gorillaz has struggled to realize its original vision of a virtual band. For audience members who expect a holographic performance at a Gorillaz concert, there are a few visuals on LED screens that pay homage to the Gorillaz characters, but that is where the animated band ends and Damon Albarn’s live performance begins. Why is this?

The single greatest barrier to Gorillaz’s original vision has always been the substantial cost of animation and producing hologram performances. You do not need to be a chartered accountant to acknowledge the eye-watering sums of money that 3D animation and holograms require. Let’s look at a few examples. Saturnz Barz was a 6-minute animation costing $800,000.[15] The video was so expensive it was immortalized as a meme on the Gorillaz subreddit.

Credit: Gorillaz Sub-reddit.

3D animations designed for a live performance in 2002 reportedly cost £300,000 to create.[16] That is just for the music videos. Holographic performance was at best, insanely expensive and at worst, technically impossible. A holographic tour planned for 2007 and 2008 was projected to cost a whopping £8,000,000 to produce.[17] It was so expensive; it did not even go ahead. In 2006, the Gorillaz did a pseudo-holographic performance with human artists who had participated in the Demon Days album at the Grammys. The lower frequencies of the music caused the holograms to jitter, meaning that the volume needed to be turned down very low. Albarn later remarked that it was “the quietest show we’ve ever played”[18].

Despite Gorillaz’s enormous success, the economics of creating an animated band have been nonsensical up to now. Each music video costs hundreds of thousands of dollars if it is 2D. 3D animation is even more costly. When it comes to holograms, it's only possible when done in one location and even then, it is a pseudo-hologram, Pepper’s Ghost, which we will examine later in the essay. When we analyze Gorillaz, the ingredients of a successful virtual band are plain for all to see. High-quality music is fundamental to a group’s success. Gorillaz’s output has amassed an enormous following in a way Kyoko Date’s did not because they have a masterclass British rock artist at the helm of the project and the writing is excellent. Kyoko Date's debut was underwhleming because the music was bad. Gorillaz's high output of evergreen content also makes them a great band to see live. Prudent management of costs is important. Gorillaz have financed the high cost of animation through record sales and traditional tours and they have not “betted the farm” on one project alone, a mistake that Horipro made. Nevertheless, the high cost of animation and holographic content looms over Gorillaz like a dark cloud. As we will examine later in the essay, this is about to change dramatically. As R3 plays out, we will see a dramatic reduction in the cost of producing 3D content occur alongside the rise of holograms as a dominant media form. 3D technologies will soon be used in some capacity for almost everything creative.

If we analyze Kyoko Date and Gorillaz side by side, we can find merit in both projects. Horipro envisioned creating a virtual artist led by a corporation which mitigated many of the risks of developing a regular artist. Although Kyoko Date was a failure, Horipro still exists as a firm today, showing that corporations can absorb the high costs that come with producing virtual bands and artists. On the other hand, the high cost of animation has historically been a struggle for Gorillaz. Gorillaz focused on creating excellent music and used fictional characters instead of an avatar representing a real human. The characters create an added layer of interest and the opportunity to create a background story. Great music is obviously central to any music project, the animation should complement the music. Gorillaz has been financially successful without the holograms.

Kyoko Date and Gorillaz give us a clear model of why virtual artists can be economic and an idea of the key ingredients involved in creating a successful virtual artist group. Virtual artist projects that have fused high-quality animation with fictional characters have met with success. One such example is the Fictional-Third-Party-Virtual-Artist, Hatsune Miku, an avatar produced by the Vocaloid company Crypton Media. Initially, Hatsune did not generate much of a buzz, but over time Hatsune has developed into an accidental media franchise worth over $100 million with a large network of avid fans.[20] According to Crypton’s website, there are over 100,000 released songs, 170,000 uploaded YouTube videos, and 1,000,000.[21] More recently, animated group combination of fictional characters and excellent music.

3D Modelling MAVE. Credit: Metaverse Entertainment

In the next section, we will examine how the ray-tracing revolution will power a new era of 3D content and game engine technologies to lower the cost of animation.

Virtual artist development is a collision of many fields. You need a solid understanding of the music industry to develop a clear virtual band concept. You also need an understanding of game development, 3D graphics and rendering. It is easy to think to yourself: I will leave that to the tech guys, but this is an enormous mistake. You need to understand 3D to make rational, economic decisions in this field. If you are developing a 3D virtual artist that looks indistinguishable from a human, for example, the cost of 3D rendering each photo would be very high. It might even be unfeasible in some cases. Basic knowledge of 3D is critical for making these types of decisions as a founder. There is another reason why an understanding of these concepts is critical. They will help you firmly grasp the meaning of the real-time ray-tracing revolution and the benefits it will bring.

In this section, we will concentrate on the basics of 3D graphics, rasterization rendering, real-time raytracing, and the implications of the real-time raytracing revolution. We will look at the technologies like virtual production that emerge when 3D graphics become indistinguishable from everyday life. I will also preface this section by saying that it is quite technical.

Computer graphics are three-dimensional representations of geometric data that are stored on a computer to perform calculations and render images.[22] 3D content like games or 3D animation is made up of many different 3D assets. An asset is a 3D representation of a three-dimensional object. If you were planning to create an animation in a game engine that re-creates the story of the Wizard of Oz, for example, you would need an asset representing Dorothy, assets for all the other characters, you would need many tree assets, a gold brick asset (multiplied many times) and so on.

Before a 3D asset can appear in a game or a film, it must first be created as a 3D model. A 3D model is created by a modeller whose work closely resembles that of a digital sculptor. A sculpture starts off with a large block of clay and they refine their piece, pinching it, squeezing it, and molding it until it has the likeness of their chosen subject. A 3D modeller does almost the same thing, except they use CAD software to achieve this. 3D modelling looks very like a type of digital sculpture. At the end of the process, modellers will have a graphical file that resembles a 3D object; however, it is just a file. It cannot be used as a 3D asset, not yet. Once the clay sculptors finish their work, they put it in a kiln for firing. In 3D graphics, a 3D model needs to be rendered before it can be used, and this is the digital equivalent of firing. Rendering involves the computer taking in all the specifications of a 3D model and generating an image (one that often looks real). Once the render is complete, the 3D asset can then be used in a piece of content. It is important to note that traditional rendering takes an enormous amount of time. One single frame (bear in mind an animation is hundreds of frames played successfully) from Toy Story 4 took 1,200 hours to render.[23]

Rendering is arguably the most important part of the 3D graphics pipeline. The rendering process we described above is general rendering. Yet the focus of this essay is on real-time raytracing, a form of real-time rendering. Instead of a computer rendering a 3D model into an asset, real-time rendering involves the rendering of a scene in real-time. Imagine you are playing a first-person shooter and you want to do a 360 turn to see if you are under attack, you can simply turn the joystick accordingly and the game will render the graphics in real-time.

For much of the video game industry’s history, games have used a real-time rendering technique known as “rasterization”. Rasterization is fast and it does a good job. With rasterization, objects on a screen are made of polygons or triangles. Computers then attempt to convert the 3D models into pixels, or dots, assigning a color to each value. Further “shading” or pixel processing is combined with the application of multiple textures to the pixel to generate the final color of the pixel. To date, rasterization has been a steady workhorse for graphics pipelines around the world. The problem is that rasterization does not handle light very well. Ray tracing is quite literally the tracing of rays of light. As a particle of light hits an object, it can split into several sub-rays. In real life, these rays make our world visually rich. In computer graphics, these rays create an enormous workload for the computer, especially the graphics processing unit (GPU). While rasterization is very poor at this, raytracing is infinitely better at it. The main point to grasp is that raytracing is fundamental to the creation of photorealistic rendering. Until recently, raytracing has been too computationally expensive to complete on consumer-grade GPUs. Nvidia’s GeForce RTX (Ray Tracing Texel eXtreme) series, released in the late 2010s, changed all that because it was the first consumer product to contain raytracing cores.

GPUs are powering the ray-tracing revolution; however, it is still incredibly expensive to apply. As Moore’s law accelerates, raytracing will become ubiquitous within all forms of 3D content. A YouTube comment from the Minecraft Raytracing Edition video below sums up the awesome power of raytracing pretty well: “RTX off: frames per second. RTX on: flames per second.”[24]

Credit: Minecraft RTX - RTX On/Off.

The raytracing revolution has coincided with the rise of game engines as the default 3D production tool. A game engine is a suite of software tools that are used specifically for game development. It is essentially a toolbox for making games. In the past, many studios developed their own engines; however, today there are a small cluster of elite game engines that have risen from the fold. Whereas game engines were once the preserve of game developers, the rapid advances in gaming technology mean that game engines now have uses in film-making, VFX, and our interest – animation. The creator of Unreal Engine, Epic Games, has been particularly aggressive in positioning Unreal Engine as the 3D engine of choice and as a key building block for the “metaverse”. The world is hurtling towards a future where almost anything creative is done using these engines. While we could spend hours delving into the many incredible technologies that game engines could enable, there are only two that interest us: animation and virtual production.

Traditional 3D CGI Animation is normally done using CAD software. The animators make minor, minute changes to each frame and then each frame is rendered. When you play all the stills concurrently at speed, it creates an animation. It is an intensely time-consuming process and incredibly expensive. High-quality 3D animation using this methodology is not cheap either. It can cost between $20,000 and $50,000 per minute.[25] Rendering is one reason for the substantial cost. With traditional animation, each frame is rendered individually, so it can take a long time. This is completely intuitive. It takes a long time to render a single frame and animations are made of many frames.

Game engines are optimized for real-time rendering meaning that they do not have any of the constraints mentioned above. Real-time rendering is faster and significantly cheaper. The game engines have a suite of tools and automation that speed up animation times. The assets in game engines can be used multiple times. This means that you can produce 3D animation for much less compared to using traditional animation methods.

Solo Chinese developer Zeng Xiancheng’s game Bright Memory: Infinite (2019) showcases this revolution in action. Xiancheng singlehandedly worked on his game for 4 years and he worked on the 3D art for another 7 years. By combining real-time technologies, unreal engine and iClone (animation automation) Xiancheng was able to produce this game for almost nothing. The game itself looks great, but the animation scenes look particularly amazing. They are pristine, raytraced and brimming with light. Bright Memory is demonstrative of the immense cost savings that game engines bring to 3D animation. It shows how raytracing technologies immensely increase the power of these engines. When you think that traditional animation costs $20,000-$50,000 per minute, Bright Memory seems like a miracle.

Bright Memory animation showreel. Credit: Zeng Xiancheng

We can observe the immense power of game engines within another concurrent trend - virtual production. Traditionally, filmmakers shot in physical locations if they needed to capture a scene in a physical location. Virtual production means you can use LED walls to render a scene in the background. The render of the location looks so realistic that you cannot tell it is not real. Filmmakers still manage regular sets; however, the background is an LED wall with the location displayed on the wall using real-time technologies. Virtual production will dramatically alter how films are made in the future. Since 2020, many studios have been forced to integrate this way of working into their workflows, so virtual production is growing rapidly. Music companies have also brought in virtual production as a means to cut costs and shoot in interesting places. For me, it is the implications of virtual production that are even more interesting. If you can render realistic images, or videos and use them for filming, why not render the artists themselves? If you are training a pop group, surely it is cheaper to create an avatar and use unreal engine’s real-time technologies to animate them? The economic implications of the real-time raytracing revolution are profound. Creators and studio executives of all kinds will be asking themselves similar questions in the near future.

On-set at Epic Games. Credit: Epic Games

On-set at Epic Games. Credit: Epic Games

The cost savings that real-time technologies bring when paired with game engines can be high. This is highly relevant to the field of virtual artist development because 3D animation has historically been the largest expense for virtual artist groups. In the past, you needed to shore up investor appetite to create a simple 3D animated music video. When Horipro first envisioned the Kyoko Date project, their thinking made enormous sense.

In the next section, we will see how virtual artist development via real-time technologies and game engines will challenge the current K-pop model because it is orders of magnitude cheaper to develop virtual artists. Historically, we noted that virtual artist development required enormous upfront costs, however, this trend will soon flip into reverse as computing power continues to compound and the real-time raytracing revolution plays out in full. This means it will soon become much more economic for music managers to deal with wholly, or partly virtual artists. The story of Scooter Braun finding a talented 13 year old singer on youtube by chance will soon seem like something from ancient history. The SB of tomorrow will just design the artist he wants in 3D.

In the next section, we will examine the evolution of pop music and the current artist development model that is ubiquitous in Korea, the current home of pop music. We focus on Korea because the influence of the East in the music industry is growing by the day. If the Kpop model is not the current gold standard for artist development, it will be very soon. We will dive into the astronomical economic costs of developing a pop group from scratch and we will then explore the difficulties of maintaining popularity. Once this historical foundation is built, we will explain how the new virtual artist development paradigm threatens the business models of the past.

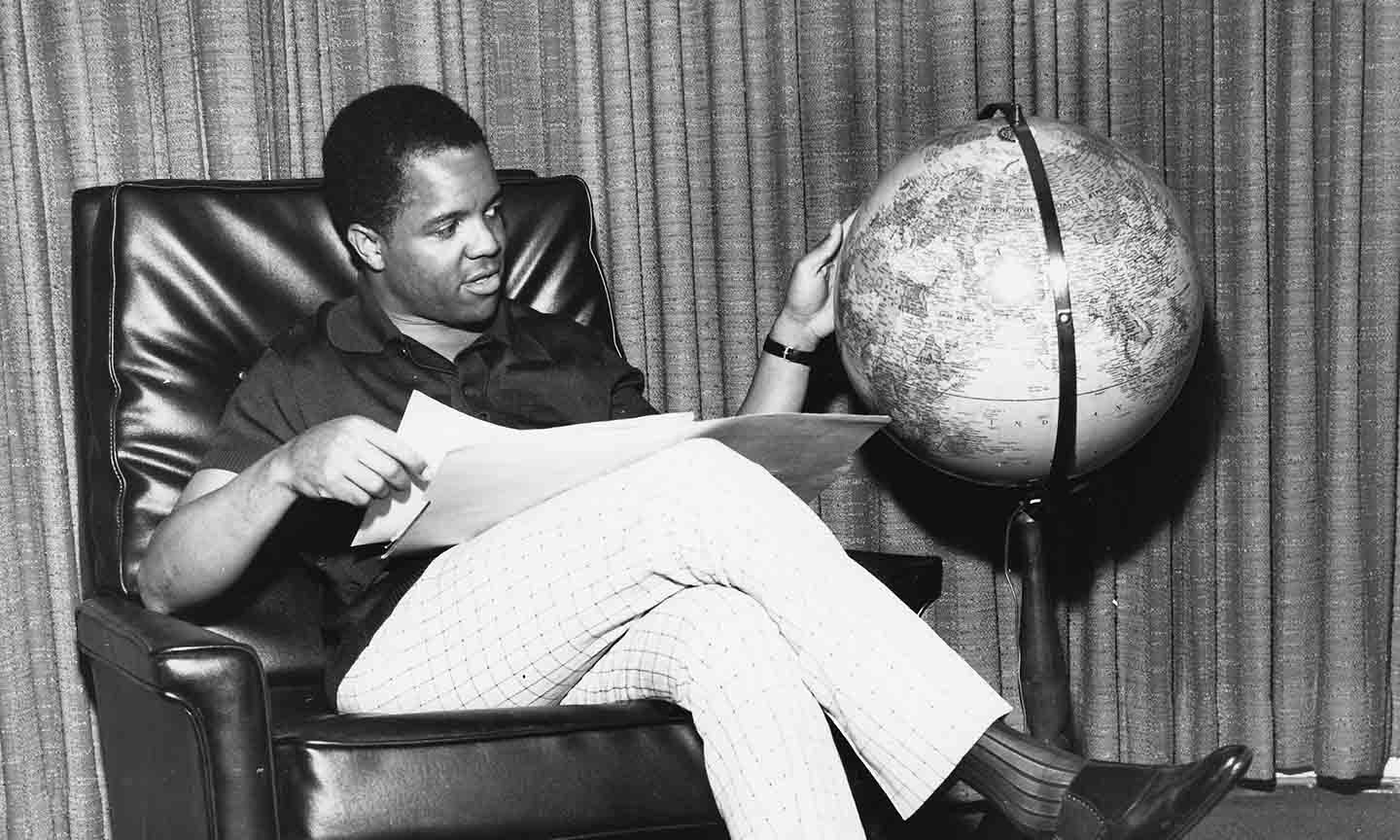

In the music industry, the motif of the factory is never far away. Hit producers of the past like Dr. Dre or Quincy Jones ran so-called “hit factories.” Contrived musical performances are derided as being taken from the “assembly line.” The assembly line analogy in pop music isn’t just a trope - the original and most successful pop label in history was modelled on the original Ford factory in Detroit. Motown Records began when Berry Gordy envisioned a music company which emulated the quality-first ethos of a car factory. Motown was short for Motor Town.

A young Berry Gordy. Credit: Rolling Stone

A young Berry Gordy. Credit: Rolling Stone

High creative standards were fundamental to the success of Motown. When asked for her favorite track, Gordy’s quality control officer, Ms. Brown, would often reply instead: “You mean which one [song] do I hate least, don’t you?”.[27] The studio was also incredibly spartan. There were few tools and staff were worked to the bone. One band, for example, the Funk Brothers, played on almost every Motown record. The image control department emphasized strict postural guidelines for artists, such as sitting upright and maintaining certain standards of propriety. Finance kept a close eye on the royalty structures, preventing young artists from accessing their funds before the age of 18 in some cases. The legal department used strict contracts to lock in artists for years and with harsh royalty terms (if the artists did lawyer up.)

In today’s world, pop culture has shifted from west to east. K-pop’s bubblegum pop songs flirt between Korean, English and sometimes Mandarin. The music is sort of a cocktail of every musical genre which includes a synthesizer. The dancing is highly choreographed and visually spectacular. But if you squint close enough, you will see that this is simply a more streamlined, more extreme version of the Motown model. Instead of a bit of personality coaching, stars in idol groups are expected to develop a distinct, unique persona – shy, sexy or funny.[28] A prominent Korean plastic surgeon estimated that 90% of K-pop hopefuls undergo surgery.[29]

Motown stars did not use trainees, however, K-pop operates by training enormous groups with success rates. As one commentator put it: “Out of 10,000 people who audition, only 100 will become trainees, and out of 100, only 10 can become a popular singer. Out of those 10, only one will really be a star”.[30]

Kpop hopefuls grind it out for a shot at the bigtime. Credit: Mashable.

While we do not want to delve into the idol industry too deeply, we can see that enormous sums of money are often spent to train these stars with a low chance of success. For those that are successful, even the slightest PR incident can result in cancellation which can easily happen because they are oftentimes not allowed to do things natural humans want to do. Even if a group is insanely successful, their shelf life is constrained by their youth, so they can only operate for a limited number of years in the best-case scenario. Continuing with the factory metaphor, I believe that the current pop music model is like a stuttering industrial factory. It is on the verge of being superseded by a streamlined alternative which places real-time raytracing and game engine technologies at the nexus of its operations. The winners of this new era of content creation will be software engineers, animators, and technologists. Whether the old guard will be able to adapt to this new world, is another question.

In the next section, we will look at how virtual artists will hypothetically be developed in the future using real-time technologies and game engines. We will explore the steps required in creating virtual artists and how they are often far more efficient than producing regular pop artists. Additionally, we will examine some of the challenges that emerge when working with virtual artists. Our focus will be on the development of Fictional-Third-Party-Virtual-Artists, the category that will benefit the most from the virtual artist revolution. The development of other categories of virtual artists is, after all, self-explanatory. For example, an artist using an avatar does not require any development, and Avatar-Driven Virtual Artist simply requires a music manager to develop 3D models of their artists.

In many cases, the artist development process will begin with internal research. A large database of all the current large artists could be pitted alongside various artist archetypes modeled on successful acts of the past. Creative directors will then search for a “gap in the market” that they can focus their creative efforts on. For example, the creative director might look for a “Britney Spears”, that is, an archetype of a young, innocent girl sincerely singing about love and romance. Once the creative director settles on the “Britney Spears” character, they begin to build the universe around their character and the character’s fictional ‘world’. The character artist will then work with the creative director to establish the concept art for the character and

Early creative choices, like the character's design or backstory, will influence the project's entire direction. The most important question is whether the artist should be fictional or a realistic avatar. As I mentioned before, hyper-realistic characters often fail to capture the small details of human interaction. Viewers can also feel the uncanny valley phenomenon, whereby imperfect humanoids produce unsettling feelings in humans. There is also a risk of backlash where users believe the avatar is real only to find out the truth later on. Fictional artists are far less threatening, avoid the uncanny valley, and are more interesting.

Once the model is complete along with the character's elaborate backstory, the creative teams can focus on the music and video, respectively. The music creation process remains consistent. However, videos can now be produced using platforms like Unreal Engine and animation integrations like iClone which increase animation efficiency. From here, the developers or developers put together the video based on the assets they have. If the project is short on money, both Unreal and iClone have some free assets and you can find others on the internet. This is a question of man-hours; however, one person could easily create a high-quality music video with enough time and dedication.

It is easy to forget the importance of great music to the project. This is a mistake. Excellent music is the lifeblood of a project. For Motown, quality control was always paramount. In K-pop, the music is the most important component. It is no different for virtual artists.

Having established these foundational elements—character, music, and video—it should be clear that the overall cost is significantly lower than producing regular artists. There is no boot camp; managers do not need to assign people personas. There is just the creator, the concept artist, and a software engineer or two. We assumed previously that all these people were separate, but could one person do everything? Absolutely. You could use stable diffusion for the concept artist, a 3D modeling AI for production, and so on. If one person created everything with AI tools, it would be much cheaper than developing real artists.

For teams working on a virtual project, they might ask: who owns the virtual artist? Ownership is a complicated topic because there is no legislation for virtual artists. This frustrates the designation of equity and adds friction to a project. You can quickly see the dangers in light of the FN Meka project mentioned earlier. The firm behind FN Meka “Factory New” had enlisted a well-known rapper, “Kyle The Hooligan,” to create the music and breathe life into their character.[33] The founders subsequently ghosted Kyle and shut him out of the record deal with Capitol Records. This is shameful behavior, but it also invites an interesting question: how might they have shared equity? Apart from splitting song royalties, there is no legal framework for splitting income for VAs earned from sponsored content. The legal infrastructure doesn’t exist.

FN Meka. Credit: virtualhumans.org

FN Meka. Credit: virtualhumans.org

Blockchain technology holds some promise in solving these types of problems. The Metaplex protocol on the Solana blockchain allows creators to enforce non-fungible-token royalties. If you create the token, you receive a small royalty every time the token changes hands in the future. Maybe there could be an integration whereby all income into the project wallet is split amongst the founders. Online creators who want to use a virtual artist may be able to “borrow” a virtual artist’s 3D model through a smart contract on the Solana ecosystem. Consumers viewing the online creators' content would know the model is the “original” because it will contain a “proof of render” watermark which will be added by the rendering company OTOY if creators choose to render their 3D content in Octane by using render token. Render deserves a second look for people interested in learning about artist rights management or anything related to this new era of media as Jules Urbach has thought a lot about where the future of media and blockchain is headed.

The rise of fictional virtual artists and Avatar-Driven Virtual Artists will be enabled by real-time rendering and game engine technologies. It is the masters of these platforms that will take the crown because technological knowledge is badly needed to succeed. This means that gaming companies have an enormous edge over others, even those without artists' development experience. While I welcome game companies to step into the area with intent, I hope virtual artists do not become a form of gimmicky content marketing by gaming companies to sell online multiplayer games. This would completely undermine this emerging field and its potential to become a completely new form of entertainment.

We have looked at the rise of virtual artists and how real-time technologies will cause the cost of 3D animation to drop dramatically. That is one part of the story. The other part is the rise of holographic media as the dominant media type of the twenty-first Century. In the final section, we will look at how the holographic revolution (holorev for short) will shape the future of media and create a monetization opportunity for emerging virtual artists.

The idea of a rock band on tour conjures up images of alcohol-induced mayhem and 7-day benders. We assume they do it as a lifestyle choice. What if they do it just to deal with touring? Touring is an enormous burden for many reasons and historically, it has split many bands. The Guns N Roses famously broke up after the legendary “Use Your Illusion” tour which lasted 28 months. It was the longest tour in history and after all the effort – they only broke even![34]

In the past, many artists attempted to supplement holograms with touring with little success. Kraftwerk mentioned a desire to have multiple robot holograms perform in different cities around the world. Gorillaz was developed with the idea of presenting the show as a hologram. In recent years, there has been the Tupac Shakur Coachella performance, the Whitney Houston hologram show, and Abba Voyage. Unfortunately, none of these are actual holograms. They are Pepper’s Ghost, a Victorian illusion, in which a video is projected onto an angled piece of glass. It is however likely that Kraftwerk and others will witness holographic technology in their lifetimes as holograms will become a dominant media format within ten years or less.

Credit: Lightfield Lab

In Silicon Valley, Light Field Lab is leading the revolution with its SolidLight holographic display platform. There is no head-tracking, no motion sickness or any signs of latency on their display panels. You can simply plug in and view the holograms as they appear. To most observers, it is indistinguishable from the objects around it. In the words of the CEO, “It’s only after you reach out to touch a Solid Light Object that you realize it’s not there,”.[35] This holographic display revolution will also happen alongside rapid advances in 5G technology. Holograms require enormous amounts of data to be transmitted in real-time. 5G enables rapid data transfer times and its low latency makes streaming happen in real-time. This paves the wave for live holographic musical performances, which require incredibly high speed internet as well as holographic technology which can meaningful project 3D content.

If holographic live performances become ubiquitous, Virtual artists stand to benefit the most. When the fields of light are streamed from the performance studio to the live area, the audience only sees the result, the hologram. It is not relevant whether they are watching an artist with 12 years of dancing experience, or whether they’re watching a singer supported by a team of animators. The audience only cares about the experience. In the hologram era, the investment in physical dancing training is not needed because professional animators can handle the holograms, so highly-trained artists are not at an advantage. All of this investment in bootcamps and dance classes is therefore wasted. The Avatar-Driven virtual artists and Third-Party-Virtual-Artists stand to benefit, because they can replicate all of this with animation teams at a fraction of the cost. Today, very few pop stars can actually sing and many stars mime on stage. If animators are animating dance moves for artists, is this not the same thing? In my opinion, it is.

Holographic concerts will democratize touring. Large tours are often highly capital-intensive, meaning established artists can produce much better shows, thus creating a durable competitive advantage. In the digital age, many artists use the same music production tools. The rich artists buy their plug-ins, whereas the less well-off artists download them from pirate bay (something I don't condone). This means that there is an ever-decreasing gap in the sound quality between professional and non-professional artists, meaning that live performance is one area where wealthy artists have a large advantage. Holographic software platforms of the future would likely use large libraries of animations for standardizing live performance like DAWs have standardized music production. This means that touring will no longer provide a strategic competitive advantage for larger artists. Just like hobbyist producers can use an array of plug-ins to sound professional, animators and 3D technicians that specialize in this area, will be able to use libraries of animators and animation-automation tools to put on an electrifying holographic performance on an extremely tight budget.

Many readers might be sceptical about holographic concerts. It is however true in music that great technological changes power creative revolutions of their own. The rise of “hip-hop” in the suburbs of NYC in the early 90s owes much to the rise of the sampler because artists could recreate the sound of a band at a fraction of the price. EDM’s surge in popularity could not have happened without the thousands of Ableton cracks being downloaded online. The rise of holograms will spark a similar revolution, because the critical elements of a live show such as dancing, lighting and incredible visuals will soon be found in animation libraries and projected using holographic technology. Readers might doubt whether audiences will accept holographic performances in favour of “real” concerts. I believe they will because many elements of modern concerts today are already “not real” anyway. The audience often cannot see the artist on stage, so they follow the concert on the large LED panels instead. Many singers today use autotune and do not sing live as a result. Many acts project interesting visuals from the LED screens as well, almost all of which are pre-recorded. Pop acts also play pre-recorded songs and if artists are bad at singing, they will sing over a tuned recording of their voice. In many cases, it is only the live audience and the visual effects that differentiate the concert from something else, but soon even these will be accessible to bedroom producers. If holograms do take over, the audience will still be there. Holographic performances will also be considerably cheaper and will take a lot of the strain from being an artist. A similar equivalent might be office workers working from home for the first time. Once they get a taste of it, they do not want to return to the office.

Holorev will touch aspects of our lives far beyond virtual artists. As the physical world and real-time raytracing inextricably intertwine, holograms will begin to dominate our lives. They will replace billboards as the dominant ad platforms, they will replace patchy zoom calls with high-fidelity visualisations and they will enter all areas of life where human contact was once central.

The virtual artist revolution does not however mean that humans will become obsolete in place of computer graphics. While the virtual artist revolution will challenge the K-pop industry due to the dramatically improved economics, I think that consumers will still be drawn towards the humanity and community of K-pop. This will become its biggest competitive advantage. No matter how hard the industry stretches the pop music model, there are still human beings training and performing for their audience.

While I tried to discuss everything in this piece, there is much that I left out. Blockchain is one area that is fascinating regarding virtual artistry, and I would be willing to bet this sector will bring incredible innovations to the field. When you see the fervour and passion that comes from fan groups of K-pop acts like BTS, it is easy to imagine a crypto equivalent in the form of a DAO (Decentralized Autonomous Organization). Digital rights management is another interesting area where blockchain could innovate. Creators of any kind could possibly “rent” an official 3D model for their music video, or for a “metaverse” event. I purposefully avoided covering the metaverse in stark detail in the essay. So much has been written on this topic that I did not feel there was much to add. Considering that Roblox and PUBG have hosted many successful virtual concerts, I do not think anyone doubts the profit potential of online events for virtual artists of all kinds.

[1] PLAVE 플레이브. 2023. “PLAVE (플레이브) ‘기다릴게’ M/v | (Wait for You).” YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cFm8fTRW_so.

[2] ecoloma. 2023. “First-Ever Filipina Virtual Model Earns Negative Reactions for Her ‘Not-So-Filipino’ Features.” POP! February 3, 2023. https://pop.inquirer.net/339527/first-ever-filipina-virtual-model-earns-negative-reactions-for-her-not-so-filipino-features.

[3] Gularte, Alejandra. 2022. “What’s Going on with FN Meka and Capitol Records?” Vulture. August 24, 2022. https://www.vulture.com/2022/08/fn-meka-dropped-capitol-records-tik-tok-rapper.html.

[4] 2023. Google.com. 2023. https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&ved=2ahUKEwjak_nbrIqCAxW6VkEAHdcmDgEQFnoECCMQAQ&url=https%3A%2F%2Ffreedesstudio.com%2Fblog%2F3d-rendering-cost-pricing-guide-with-key-rendering-types%2F&usg=AOvVaw0FPRTPLd6LtVjOrN2dASoy&opi=89978449.

[5] “Netflix Canceled the Gorillaz Movie, but at Least They’ll Charge You Extra to Let Your Parents Use Your Account.” n.d. The FADER. Accessed October 22, 2023. https://www.thefader.com/2023/02/21/netflix-canceled-gorillaz-movie.

[6] Brown, Lane. 2017. “Damon Albarn and Noel Gallagher on the Making of Gorillaz’s ‘We Got the Power.’” Vulture. April 25, 2017. https://www.vulture.com/2017/04/damon-albarn-and-noel-gallagher-on-gorillazs-we-got-the-power.html.

[7] Ingham, Tim. 2019. “Nearly 40,000 Tracks Are Now Being Added to Spotify Every Single Day - Music Business Worldwide.” Music Business Worldwide. MBW. April 29, 2019. https://www.musicbusinessworldwide.com/nearly-40000-tracks-are-now-being-added-to-spotify-every-single-day/.

[8] “Kyoko Date: The World’s First Virtual Pop Star.” n.d. EW.com. https://ew.com/article/1997/05/16/kyoko-date-worlds-first-virtual-pop-star/.

[9] Wolff, W. n.d. Review of Kyoko Date - Virtual Idol: A Retrospective View. Accessed October 23, 2023. https://www.wdirewolff.com/jkyoko.htm.

[10] “時代を席巻した[元・ネット有名人]の今【その1】 | 日刊SPA!” 2012. Web.archive.org. April 23, 2012. https://web.archive.org/web/20120423043606/http://nikkan-spa.jp/1939.

[11] Kelder, Robert. 2001. Review of Gorillaz Has a Hit Album, but Do They Really Exist? August 7, 2001. https://www.chicagotribune.com/news/ct-xpm-2001-08-07-0108070006-story.html.

[12] “10 Iconic Gorillaz Moments.” n.d. Mixmag. Accessed October 22, 2023. https://mixmag.net/feature/10-iconic-gorillaz-moments/2.

[13] Wikipedia Contributors. 2019. “Gorillaz.” Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation. April 14, 2019. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gorillaz.

[14] “Biggest-Selling Virtual Band.” n.d. Guinness World Records. https://www.guinnessworldrecords.com/world-records/77801-biggest-selling-virtual-band.

[15] Brown, Lane . 2017. Review of ORAL HISTORY APR. 25, 2017 Damon Albarn and Noel Gallagher on the Making of Gorillaz’s “We Got the Power.” April 25, 2017. https://www.vulture.com/2017/04/damon-albarn-and-noel-gallagher-on-gorillazs-we-got-the-power.html.

[16] Wikipedia Contributors. 2019. “Gorillaz.” Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation. April 14, 2019. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gorillaz.

[17] “Cancelled 2007 Virtual Tour.” n.d. Gorillaz Wiki. https://gorillaz.fandom.com/wiki/Cancelled_2007_Virtual_Tour.

[18] “Cancelled 2007 Virtual Tour.” n.d. Gorillaz Wiki. https://gorillaz.fandom.com/wiki/Cancelled_2007_Virtual_Tour.

[19] “Cancelled 2007 Virtual Tour.” n.d. Gorillaz Wiki. https://gorillaz.fandom.com/wiki/Cancelled_2007_Virtual_Tour.

[20] “SankeiBiz: Hatsune Miku Has Earned US$120 Million+.” 2022. Anime News Network. May 2022. https://www.animenewsnetwork.com/interest/2012-03-27/sankeibiz/hatsune-miku-has-earned-us%24120-million+.

[21] Crypton Future Media. n.d. “About HATSUNE MIKU | CRYPTON FUTURE MEDIA.” Ec.crypton.co.jp. https://ec.crypton.co.jp/pages/prod/virtualsinger/cv01_us.

[22] Wikipedia Contributors. 2019. “3D Computer Graphics.” Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation. January 20, 2019. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/3D_computer_graphics.

[23] published, Tom May. 2021. “8 Mind-Boggling Facts about the Making of Toy Story 4.” Creative Bloq. January 26, 2021. https://www.creativebloq.com/news/mind-boggling.toy-story-4-facts#.

[24] “Minecraft RTX - RTX On/off Gameplay.” n.d. Www.youtube.com. https://youtu.be/Vgu6pLYNrPE?si=8JXPOiVSFdHe0iwb&t=78.

[25] “How Much Does Animation Cost per Minute of Video?” n.d. ProductionHUB.com. https://www.productionhub.com/blog/post/how-much-does-animation-cost-per-minute-of-video.

[26] “Making the First Virtual Idol.” n.d. Www.youtube.com. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yptPDsuQPa8.

[27] Boyce, Anika Keys. 2008. Review of “What’s Going On”: Motown and the Civil Rights Movement. PDF, Boston College University Libraries. http://hdl.handle.net/2345/590, p. 40.

[28] Griffiths, James. 2018. “Can K-Pop Stars Have Personal Lives? Their Labels Aren’t so Sure.” CNN. September 22, 2018. https://edition.cnn.com/2018/09/21/entertainment/kpop-dating-hyuna-edawn-music-celebrity-intl/index.html#.

[29] Mundy, Simon . 2015. Review of K-Pop’s Production Line for Gangnam Style Wannabes. Edited by Roula Khalaf. Financial Times (blog). February 2, 2015. https://www.ft.com/content/70a4e97a-a7da-11e4-97a6-00144feab7de.

[30] Mundy, Simon . 2015. Review of K-Pop’s Production Line for Gangnam Style Wannabes. Edited by Roula Khalaf. Financial Times (blog). February 2, 2015. https://www.ft.com/content/70a4e97a-a7da-11e4-97a6-00144feab7de.

[31] Markets, Research and. n.d. “Global $20 Billion K-Pop Events Market to 2031: Breakdown by Music Genre, Revenue Source and Gender.” Www.prnewswire.com. Accessed October 22, 2023. https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/global-20-billion-k-pop-events-market-to-2031-breakdown-by-music-genre-revenue-source-and-gender-301820881.html.

[32] “How Much Does It Cost to Debut a K-Pop Group?” 1470. Soompi. 1470. https://www.soompi.com/article/883639wpp/much-cost-debut-k-pop-group.

[33] Corry, Kristin. 2022. Review of We Spoke to the Actual Artist behind FN Meka, the Controversial AI Rapper. August 25, 2022. https://www.vice.com/en/article/qjkjzw/ai-rapper-fn-meka-kyle-the-hooligan-interview.

[34] Giles, Jeff . 2015. Review of Duff McKagan Says Guns N’ Roses’ “Use Your Illusion” Tour Took Two Years to Break Even Read More: Duff McKagan Says Guns N’ Roses’ “Use Your Illusion” Tour Took Two Years to Break Even | Https://Ultimateclassicrock.com/Guns-n-Roses-Use-Your-Illusion-Tour/?Utm_source=Tsmclip&Utm_medium=Referral. January 6, 2015. https://ultimateclassicrock.com/guns-n-roses-use-your-illusion-tour/.

[35] “Light Field Lab Raises $50M to Manufacture Its SolidLight Holographic Displays.” 2023. VentureBeat. February 8, 2023. https://venturebeat.com/games/light-field-lab-raises-50m-to-manufacture-its-solidlight-holographic-displays/.